Crowdfunding is everywhere these days. People raising money for causes they believe in, to start a business, meet an idol or, most often, pay for health-care costs.

From raising money to pay for cancer treatment to helping someone pay for unattainable medical bills to paying for research into a rare disease, raising money for health-care costs has become so routine, a recent Atlantic article says doctors are sometimes recommending it.

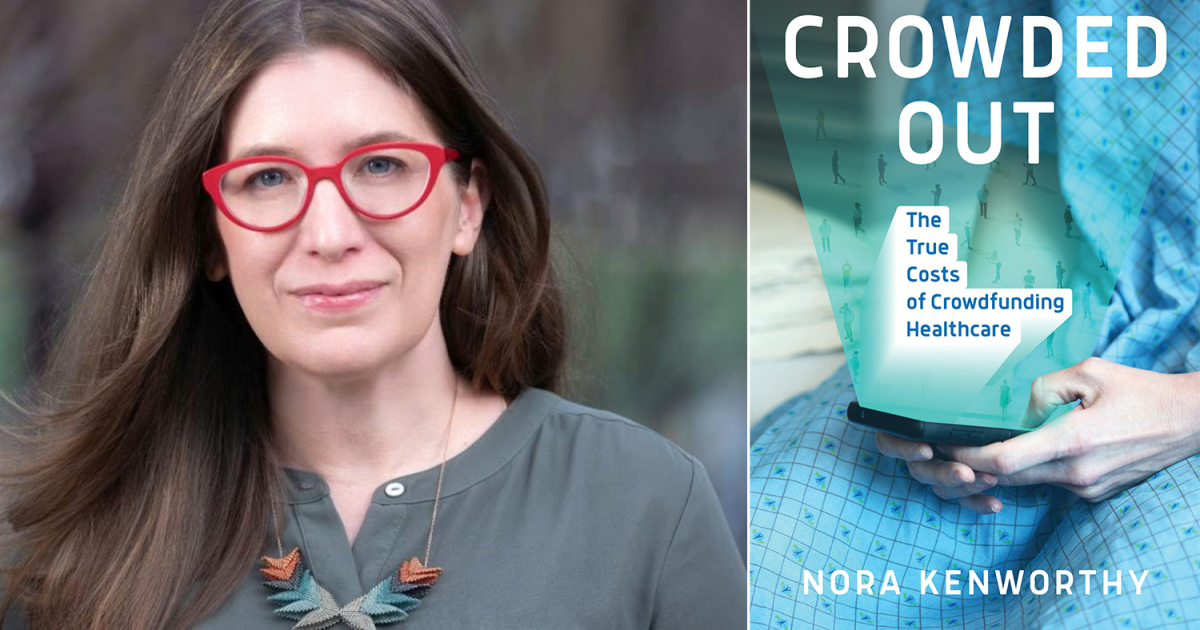

Nora Kenworthy, associate professor in the University of Washington’s School of Nursing and Health Studies, says that speaks volumes about our health-care system. She wrote “Crowded Out: The True Costs of Crowdfunding Healthcare,” and spoke more about the issue with The Show’s Lauren Gilger.

Full conversation

NORA KENWORTHY: I started looking at crowdfunding sites about 10 years ago. So this was quite a while before most people had heard of sites like GoFundMe. One of the earliest campaigns I came across was actually on a flier, like a paper flier, posted to a telephone pole in my neighborhood.

At that time, GoFundMe had so little kind of name recognition that one of the things they offered to fundraisers was that they could kind of print out these sort of flyers of their campaigns with tear-off tabs at the bottom. But even at that early date, I was noticing that a very large proportion of campaigns that I was seeing on sites like GoFundMe were for medical needs and expenses.

LAUREN GILGER: Talk a little bit about how this works. Like I think people are aware that they exist, but it’s not like if you raise money on a site like GoFundMe, you will always raise enough to pay for what you need to pay for or that you’re going to get all of the money that people donate to you, right.

KENWORTHY: Yes. So sites like GoFundMe operate differently than sites like for example, Kickstarter, right? So if you’re fundraising on Kickstarter, you actually have to hit your goal in order to get your money.

Whereas on GoFundMe, you get whatever people donate to you, minus some fees and percentages that are taken out of donations. And sites like GoFundMe will encourage people to set a relatively low goal for their campaign. So, you know, even if I perhaps am facing a very significant out-of-pocket cost for say cancer care or something, you know, in the tens of thousands of dollars, if I do the kind of the steps of like how to set up a campaign on GoFundMe will largely tell me to set a pretty low goal of a couple of thousand (dollars).

And often that’s because I think GoFundMe wants people to have a successful experience, right. And recognizes that most people who start campaigns on the site are not going to raise tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of dollars. You know, most people can expect to raise, you know, maybe a couple of thousand. But a lot of people actually raise much less than that. So, about 40% of campaigns raise $70 or less.

You know, people see campaigns in their midst that are very popular doing incredibly well. Those are the campaigns that we tend to see on social media and in the news and it raises our expectations of what we can expect from the platform. And unfortunately, there are just a lot of people using crowdfunding right now.

And often they are reaching out to networks of people like themselves who may also have a lot of financial insecurity and may have trouble donating significant amounts to their campaign.

GILGER: Right. Right. Talk about some of those blockbuster campaigns on sites like these, like there have been some really famous ones that people have probably heard of and they’re often also like, often tied to major cultural moments.

KENWORTHY: Right. Yes, I think the, the last one that went really viral for medical reasons was probably Mary Lou Retton’s. So she was hospitalized and is a former Olympic gymnast. And her daughter started a campaign for her, it raised millions of dollars very quickly.

But I think for a lot of people, it also raised questions about how is it that it often seems that, you know, people who already have a lot of social status or celebrity are doing most on this platform. I think also it exposed Mary Lou Retton and her family to a lot of scrutiny about why it was that she needed to start a GoFundMe in the first place.

And so in that experience, she’s actually not alone. I talked to a lot of crowd funders who say, you know, yes, I raised some money, but I also face these really hard questions or these kind of judgments from the crowd about why it was that I needed to do this.

GILGER: So there’s like a stigma aspect here, even when people turn to this very public form of, of crowdfunding, of raising money.

KENWORTHY: Yeah. And I, I think if I was gonna extrapolate across, you know, thousands and thousands of campaigns that I’ve looked at, I would say one of the most common kind of emotional expressions that I see is one of shame. You know, people feeling ashamed about asking for help, ashamed that they maybe have gotten to that place in the first place.

It’s a common cultural phenomenon in the United States for people to feel a lot of shame about needing to ask for help. Unfortunately, and most people who are asking for help and GoFundMe really are kind of asking because they have no routes to turn a lot of the time, right?

GILGER: So talk a little bit about your research on, on the other side of this, right, which is like what this says about the American health-care system and, and people who even have insurance ending up in situations like this.

KENWORTHY: Yeah. So I think there’s a couple of different things going on here. So first of all, you know, we do know that even for people who are insured, the cost of care when you get extremely ill or need extensive medical procedures, often cannot be paid or afforded out of pocket. So oftentimes people are looking at, you know, bills of tens of thousands of dollars, if not hundreds of thousands of dollars.

One of the other things is that, you know, because a lot of Americans have health care that’s provided through their employer, when they get too sick to work, they then also lose their insurance oftentimes. And so I do see a lot of campaigns for people, you know, for example, who are going through cancer treatments and have suddenly lost their insurance because they’ve lost their job.

Then there’s this very substantial proportion of Americans who are either uninsured or underinsured, which means they don’t have enough insurance to really cover, you know, crisis care or catastrophic care and those people as well, you know, are being slapped with enormous bills.

So for example, I talk in the book with one woman who had a premature baby. And you know, she and the baby had to be sort of life flighted to a NICU because they were in a very rural area. And she was looking at like bills of more than $1 million for her care. And that’s not uncommon to see on, on sites like GoFundMe.

GILGER: Wow. I wonder, like do campaigns like this, do crowdfunding efforts for health care exist very much in other countries?

KENWORTHY: They do but they are different. So I would say in countries that have better public health insurance systems than we do, so for example, Canada or European countries, there’s still crowdfunding. There’s less of it overall and it tends to focus on things that are not covered by the public insurance system. So that might be more experimental treatment or nontraditional care or people who are trying to get care faster than they’re able to within the public system.

But there’s other what I call market-driven health-care systems like ours. For example, in China or in India where crowdfunding platform are thriving in part because so many people need to turn to it for medical care, right?

GILGER: So let me ask you about that lastly here, which is the, the money side of this for these companies. Like how much money does a site like GoFundMe make off of this like, what do the profits look like?

KENWORTHY: So it’s really hard to tell. GoFundMe is a privately traded company. Most of what we have to go off of is their own statements about how much money has been raised. I think this year ago FMI said that about $30 billion had been raised on its platform since 2010. So we’re talking big money, but it’s very hard to tell how much they raise from campaigns and also how they raise money from campaigns. So they asked for a tip from donors. They collect some money and fees from each campaign. But we don’t know exactly like, for example, how much money they make off of this vast trove of user data, for example, that they’re sitting on, given how many hundreds of millions of people have used the site.

KJZZ’s The Show transcripts are created on deadline. This text is edited for length and clarity, and may not be in its final form. The authoritative record of KJZZ’s programming is the audio record.

-

Last month, a judge determined that AHCCCS (like access) – Arizona’s version of Medicaid — had improperly issued contracts to health care companies that provide long-term care services to 26,000 older adults and people with physical disabilities. AHCCCS has until early next week to decide what it will do, leaving some families worried and uncertain.

-

Organ donation rates are typically low among Hispanic patients. That’s why a Phoenix hospital is urging Hispanic residents to become donors.

-

While between 10,000 and 20,000 cases are reported to the CDC every year, a vaccine for Valley fever is potentially getting closer to becoming a reality.

-

State health officials are echoing guidance from the CDC in light of what it says is the largest outbreak of Listeria since 2011. Almost 60 people have been sickened, including one in Arizona.

-

Young girls are buying up anti-aging products they see promoted on social media, with harmful effects for their skin — and their mental health.